Growth of Women in Power Stagnates in a Landmark Election Year

30 DEC 2024

Originally reported by BBC News, this article highlights the critical issue of declining female representation in global politics, based on data from the Inter-Parliamentary Union (IPU) and UN Women.

(Source: Inter-Parliamentary Union Data)

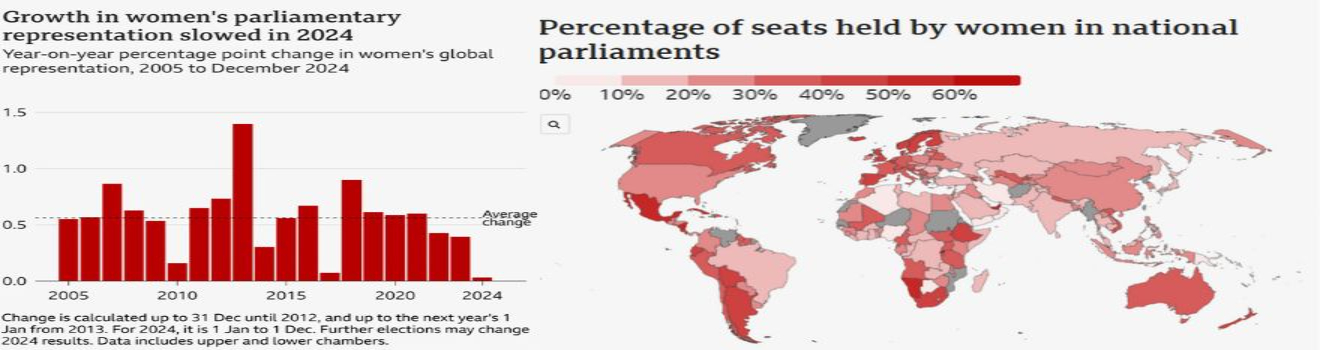

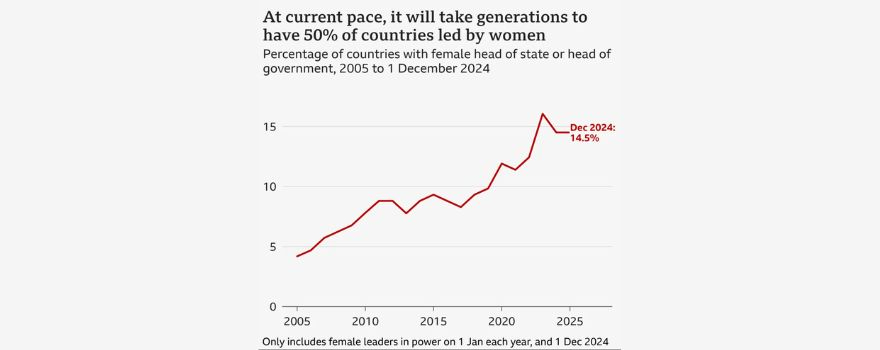

In 2024, nearly half of the world's population, around 3.6 billion people participated in significant elections. However, the year also marked the slowest rate of growth in women's political representation in two decades.

Out of the 46 countries where election results have been confirmed, 27 saw a decline in the number of women elected to parliament. Among these nations were prominent democracies like the United States, Portugal, Pakistan, India, Indonesia, and South Africa. Even the European Parliament, for the first time in its history, experienced a reduction in female representation.

The data, compiled by the Inter-Parliamentary Union (IPU)—a global organization that tracks parliamentary statistics—reveals a concerning trend: nearly two-thirds of these countries reported a drop in female parliamentary representation.

While some nations such as the United Kingdom, Mongolia, Jordan, and the Dominican Republic registered gains in female political representation, the overall global growth was negligible, standing at just 0.03%. Mexico and Namibia made history by electing their first female presidents, but the gains were overshadowed by losses elsewhere.

Globally, women now hold 27% of parliamentary seats, with only 13 countries approaching gender parity. Notably, the Pacific Islands remain the region with the lowest proportion of female parliamentarians, averaging just 8%. Tuvalu, for example, lost its sole female parliamentarian, Dr. Puakena Boreham, leaving the nation with no women in government.

Gender quotas have proven effective in boosting female representation in some cases. Mongolia, for instance, increased its proportion of women in parliament from 10% to 25% after implementing a mandatory 30% candidate quota for women. On average, countries with gender quotas elect 29% women, compared to 21% in those without such measures.

Mexico is a shining example of how political will and quotas can make a difference. Gender parity in its parliament was achieved in 2018 when then-President Andrés Manuel López Obrador championed equal representation.

While parliamentary representation has seen some progress, women remain underrepresented in ministerial roles, which are pivotal in shaping societal outcomes. According to Julie Ballington of UN Women, women are often limited to portfolios related to human rights, equality, and social affairs, while critical areas like finance and defense remain predominantly male-dominated.

“This is a missed opportunity,” Ballington asserts, emphasizing that diverse leadership could lead to more balanced and effective governance.

(Source: UN Women)

Several systemic barriers continue to impede women's participation in politics. Research highlights an "ambition gap," with women less likely than men to see themselves in leadership roles without external encouragement. This lack of self-perception, coupled with the absence of mentors, further deters women from entering the political arena. Financial constraints also play a significant role. Campaign financing is often more difficult for women to secure, and traditional caregiving responsibilities place additional burdens on female candidates. Few parliaments globally offer maternity leave, which discourages women from pursuing political careers.

Electoral systems also influence outcomes. Proportional representation (PR) and mixed systems are more likely to elect women than first-past-the-post models. Countries with PR systems often incorporate gender quotas, which have proven effective in bridging the gap.

Increasing attacks on women in public life, both online and offline, pose a significant challenge. In Mexico, where election violence is already prevalent, women politicians faced targeted gender-based violence and disinformation campaigns designed to tarnish their reputations. Such hostility creates a "chilling effect," discouraging younger women from entering politics.

South Korea provides another example of backlash against women's political advancement. While the country saw a modest increase in female representation, the perception of "reverse discrimination" among young men fueled anti-gender sentiments during the elections.

The underrepresentation of women in politics isn't just a matter of fairness; it impacts societal outcomes. Research shows that gender diverse groups make better decisions, and boards with balanced representation lead to higher profits. In peace negotiations, women's substantive involvement has been linked to more sustainable outcomes.

“When women are in the room, peace deals are more likely to happen and more likely to last,” says Dr. Rachel George, an expert on gender and politics at Stanford University.

The broader implications of this stagnation extend beyond politics. Julie Ballington from UN Women encourages a shift in perspective: rather than focusing on women’s underrepresentation, it’s essential to address the systemic overrepresentation of men in political spaces.

Addressing these challenges requires not only policy changes, such as mandatory gender quotas and better support for women in office, but also a cultural shift in how leadership is perceived.

The stagnation observed in 2024 is a reminder that progress, while achievable, remains fragile. To sustain and accelerate growth, concerted efforts are needed to dismantle barriers and create an environment where women can thrive in politics.

1733832862.jpg)

1731489929.jpg)