Yashoda Devi and the Forgotten Voices of Women's Health in Colonial India

06 FEB 2025

Yashoda Devi brought Ayurveda and women's sexual health into public discourse in colonial North India through her writings and dispensary. Her work addressed societal norms while navigating the constraints of her time.

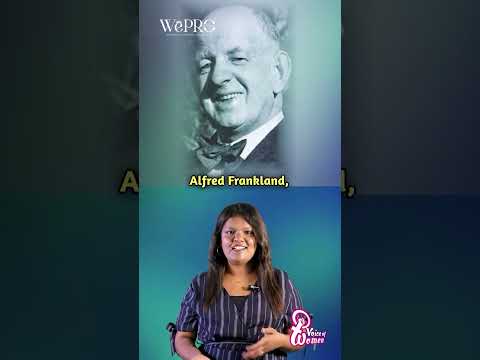

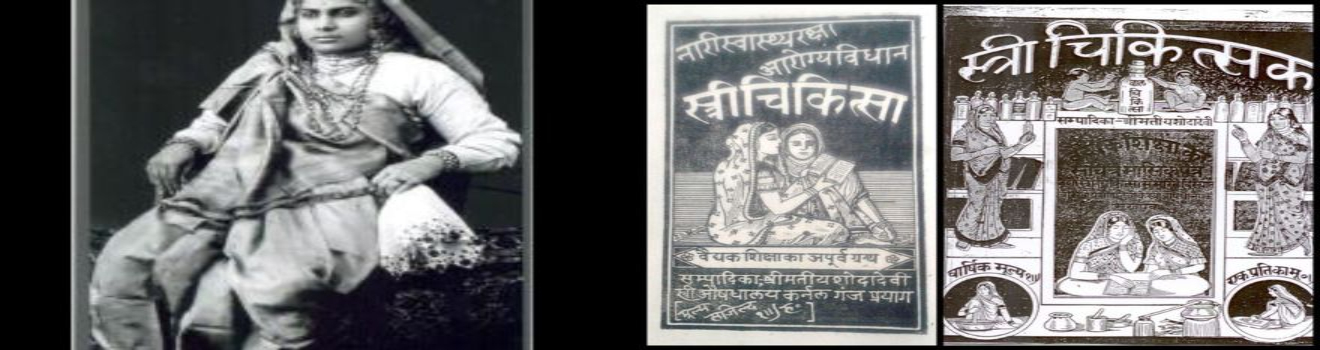

L: Yashoda Devi in 1921. (PC: Samir Sharma, Yashoda Devi's great-grandson) R:Women sharing medical knowledge and preparing remedies. (PC: Yadhoda Devi, Dampati Arogyata; Yashoda Devi, Nari Dharmashastra Grh-Prabandh Shiksha (Education on Home Management for Women), Allahabad: Devi Pustakalaya, 1931, back cover)

There are stories that remain buried in the folds of history, echoing only in the margins of scholarly texts, their presence whispered but never truly heard. Yashoda Devi's story is one such narrative—a woman who, in the quiet corridors of Ayurveda and the bustling world of print, created a space where women could speak of their bodies, their health, and the unspoken weight of conjugal life. In colonial north India, where the printed word was a powerful tool of the dominant social order, she carved a path for herself, not by merely participating in the existing structures but by altering their very texture.

Before the 1920s, Hindi literature had been an elite enterprise, restricted in scope and readership. The growth in literacy and print culture during the 1920s and 30s altered this landscape, leading to a surge in literary journals, political weeklies, and dailies. Allahabad, a city teeming with the fervor of nationalist movements, became the nucleus of this transformation, where the printed word reflected the aspirations and anxieties of the time. Yet, even as Hindi literature flourished, it remained a space dominated by the upper caste, middle-class men who dictated its themes and discourses. Women, when they wrote, often reinforced patriarchal ideals of family, duty, and nationalism. But within this male-dominated domain, a quiet revolution was taking place. The emergence of women’s journals, though initially shaped by patriarchal ideals, gradually became spaces of autonomy, where women wrote of their experiences, concerns, and aspirations.

It was within this evolving public sphere that Ayurveda, once an oral tradition passed through generations, found its way into print. By the 1930s, the number of Hindi journals dedicated to Ayurveda had surged, transforming it into an accessible form of medical knowledge. These texts, however, were more than just medical guides—they were entangled with the nationalistic desire to reclaim India’s ancient wisdom, positioning Ayurveda as a symbol of cultural pride. Amidst this growing literature, Yashoda Devi emerged as a distinct voice. Ayurveda had long been a male-dominated field, but within the domestic sphere, women had always been its informal practitioners, tending to the health of their families with remedies passed down through generations. It was in this intersection between domestic healing and formal Ayurvedic discourse that Yashoda Devi positioned herself.

Trained in Ayurveda by her father, Yashoda Devi founded the first Stri Aushadhalaya (Dispensary for Women) in Allahabad around 1908. She went on to establish a female Ayurvedic pharmacy and a publishing house, Devi Pustakalya, through which she authored over fifty books addressing women’s sexual and reproductive health. Her most popular journal, Stri Chikitsak, reached a circulation of 5000 copies per month—a remarkable feat in an era when women’s voices were often confined within the home. Through her writings, she introduced a discourse that had long been absent from Ayurvedic texts: the study of menstrual health, miscarriages, vaginal infections, and sexually transmitted diseases. Yet, despite her immense contribution, she was kept at arm’s length by the larger Ayurvedic institutions of the time. The Ayurvedic Mahamandal and Mahasammelan, bastions of traditional male authority, refused to recognize her work, reinforcing the rigid gender hierarchies that governed the field.

Covers of some books by Yashoda Devi.

Her engagement with Ayurveda, however, extended beyond medical concerns and into the domain of social reform. Her writings became a part of the larger sexology literature emerging in early 20th-century north India—a field deeply intertwined with the tensions between colonial and indigenous attitudes toward sexuality. Many of these texts, rooted in the Kama Shastras, reinforced Brahminical notions of gender and caste, shaping the way sexuality was understood and discussed. Yashoda Devi’s writings echoed some of these hierarchical structures, yet she also used Ayurveda as a tool to challenge patriarchal sexual norms.

Her work carried within it a paradox. On one hand, she promoted the nationalist ideal of the educated woman, a guardian of domestic order and moral purity. On the other, she openly discussed female sexuality, dismantling the silence that had long enshrouded it. Through detailed questionnaires, personal examinations, and intimate letters from women seeking her guidance, she pieced together a narrative of female suffering—stories of women whose husbands demanded sex against their will, of those blamed solely for infertility, and of those struggling with the psychological trauma of sexual violence.

She did not shy away from critiquing male sexual behavior, challenging the unchecked entitlement of men in the marital bed. Her writings emphasized the importance of consent, arguing against the cultural norm that placed women in subservience to their husbands’ desires. She spoke of foreplay, of the necessity of female pleasure, and of the role of mutual participation in a conjugal relationship. In doing so, she brought the private into the public, shattering the rigid boundary that had long confined women’s sexual experiences to the four walls of their homes.

Yet, her narrative was not without its contradictions. While she spoke against male dominance, she also upheld certain restrictive ideas about sexuality, condemning masturbation and non-procreative sexual practices. Her perspective was shaped by the nationalist discourse of the time, which linked sexual discipline with moral and national strength. In her quest to carve out a space for women’s health, she simultaneously reinforced heteronormative ideals, failing to step outside the biases of her era.

This tension in her work—between challenge and conformity, progress and constraint—perhaps explains why she remains an obscure figure in contemporary discourse. But to dismiss her solely for her limitations would be an injustice. She was a woman who, in a time of silence, spoke; who, in a space dominated by men, wrote; who, in a society that saw women’s bodies as subjects of control, created avenues for discussion. She encouraged women to step beyond the confines of their homes, to seek medical treatment, to write to her, to engage with their own health in ways previously denied to them. She provided them a place of respite, a rest house where they could stay during their treatment, a space that, even if momentarily, allowed them autonomy over their own bodies.

The contradictions within Yashoda Devi’s work are not failures but reminders of the complexities of resistance. They remind us that the past is not a linear story of progress but a layered history of negotiations, compromises, and quiet rebellions. Her legacy, though fractured by the biases of her time, stands as an intricate tapestry of voices once silenced, of whispered concerns turned into printed words, and of a woman who, despite the constraints around her, dared to write of women’s health, sexuality, and desire in a world that often wished her silent.

References:

1. Gupta, C. (2020). Vernacular Sexology from the Margins: A Woman and a Shudra. South Asia: Journal of South Asian Studies, 43(6), 1105-1127.

2. Gupta, C. (2005). Procreation and Pleasure: Writings of a Woman Ayurvedic Practitioner in Colonial North India. Studies in History, 21(1), 17–44.

3. Ishita, P. (2020). Introduction to ‘Translating Sex: Locating Sexology in Indian History’. South Asia: Journal of South Asian Studies, 43(6), 1093-1104.

4. Pande, I. (2018). Time for Sex: The Education of Desire and the Conduct of Childhood in Global/Hindu Sexology. In V. Fuechtner, D. Haynes E., & R. Jones M., A Global History of Sexual Science, 1880-1960. University of California Press.

1731672691.jpg)